The virtual contained in the cells and screens is waiting for the touch of the other body to unfold.

Notes on the Unfolding Flesh is a collection of reflections on montage as a process of cutting through the chaos, bodies, space, and time, alongside the ongoing philosophical, artistic, and scientific quest to understand what it means to be a body. Montage here is thought in terms of world-building through an act of cutting and re-assembling. It refers not only to a technique of image-making like photography or video editing, but it also signifies a process that creates conditions for the new worlds to emerge, pregnant with potentialities that are waiting to be actualised.

According to Joanna Zylinska, perception is a site where cutting and stitching takes place: ‘our visual apparatus introduces edges and cuts into the imagistic flow: it cuts up the environment so that we can see it, and then helps us stitch it back together again.’11 Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017), p. 42. By recognizing the role of the insertion of edges into a nonconscious flow of vision, Zylinska proposes to consider a cut in creative practice more than a technique but as ‘an ethical imperative’ to ‘recut the world anew, to a different size and measure.’22 Joanna Zylinska, p. 44. The notion of the Cut! as an ethical imperative allows to conceptualise photography, video editing, sculpture and other creative practices, as a form of world re-building:

The process of cutting is one of the most fundamental and originary processes through which we emerge as “selves” as we engage with matter and attempt to give it (and ourselves) form. Cutting reality into small pieces—with our eyes, our bodily and cognitive apparatus, our language, our memory, and our technologies—we enact separation and relationality as the two dominant aspects of material locatedness in time. 33 Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska, Life after New Media: Mediation As a Vital Process (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), p. 75.

The process of cutting as a mode of giving form, re-shaping and re-building invites us to consider reality in terms of assembled heterogeneous surfaces.

Reflections on the question what it means to be a body follows Jean-Luc Nancy’s reconceptualization of corporeality.44 Jean-Luc Nancy, Corpus, trans. by Richard A. Rand (Fordham University Press, 2008) It offers to consider the body outside the ontotheological body proper, and instead invites to reconsider corporeality in terms of multiplicity, originary technicity and fragmentation – corpus instead of le corps. Nancy’s corporeal ontology introduces the skin surface not as a boundary between the inside and the outside, but as a site where the making of sense of existence takes place, situating being a body in terms of relationality, as being neither inside nor outside but a threshold itself. It is ‘the site, or locus of interconnection, of tools or apparatus, and it is this interconnection which is the happening of the body.’55 Ian James, The Fragmentary Demand: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy (Stanford Therefore, the body is also a screen – we are circulating via the touchscreens, stretched as a translucent skin surface across the globe. It acquires a quality of an elastic fold, always in relation to itself as exteriority, as an affective surface: ‘it is a skin, variously folded, refolded, unfolded, multiplied, invaginated, exogastrulated, orificed, evasive, invaded, stretched, relaxed, excited, distressed, tied, united.’ 66 Jean-Luc Nancy, Corpus, p. 115.

/The Unknown: Interiority

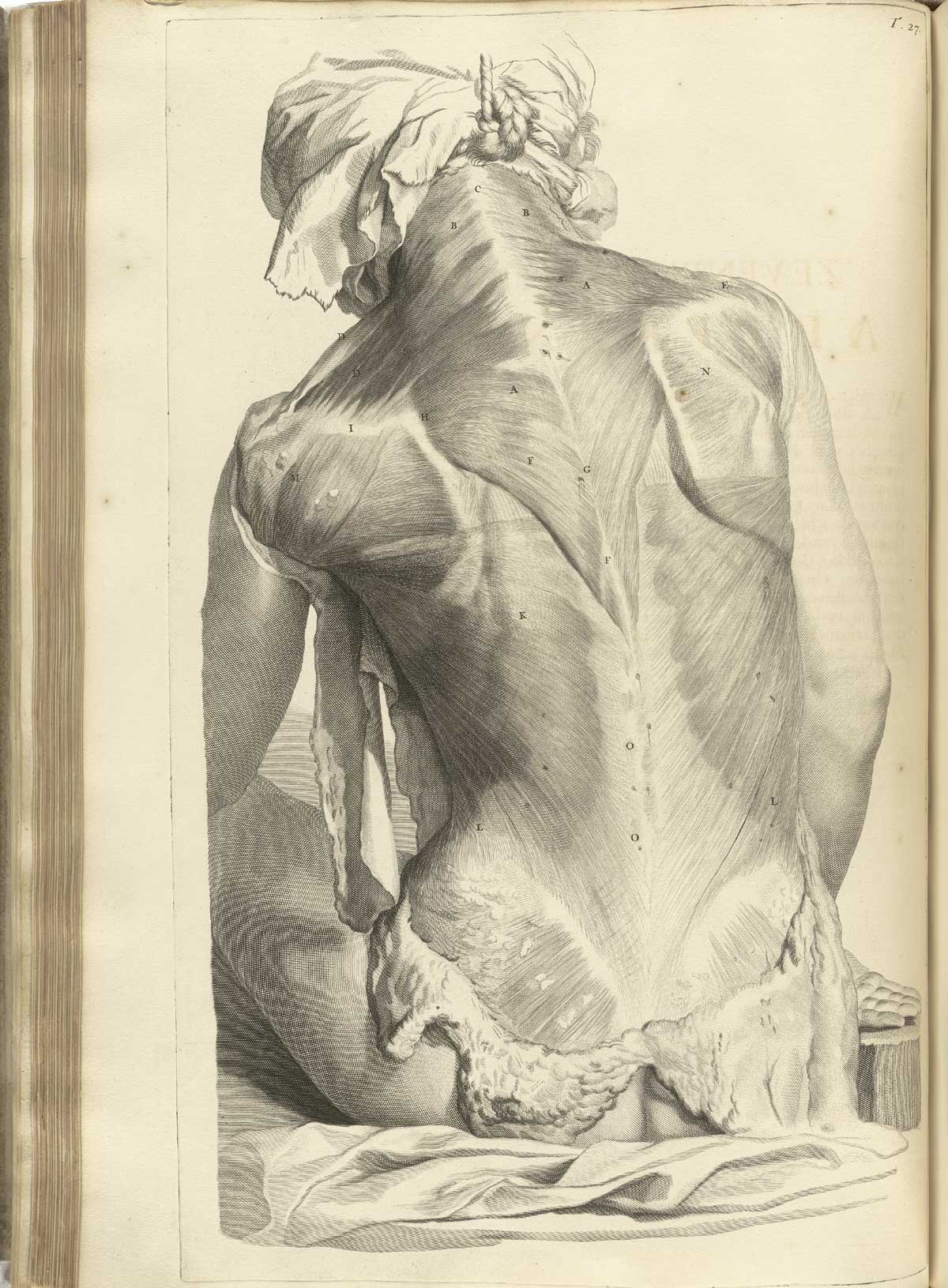

Treatment of the body as a living garment can be traced via Mario Perniola’s thoughts on baroque erotics of dressing. The process of anatomical denudation is inseparable from the desire of dressing with the folds: ‘The transit […] between clothing and nudity shows up in two fundamental ways: in the use of the erotics of drapery or attire, as we see in Bernini, and in the depiction of the body as a living garment, as we see in anatomical illustrations.’77 Mario Perniola, ‘Between Clothing and Nudity’, in Fragments for a History of the Human Body (Part Two), edited by Michel Feher and others (NY: Zone Books, 1989), pp. 237-265, (p. 253).

8 Perniola, Fragments for a History of the Human Body, p. 259. In the latter, the body displays itself through the unfolding of inner surfaces layer by layer, exposing the force of ‘The erotics of dressing [which] go beyond the skin and dress the insides of the body. Even the underside of the skin, delicately folded back to face outward, remains clean and bloodless.’8 This transit between the drapery and the flesh demonstrates the desire to conquer the unknown by folding it into an object of knowledge, which turns the body inside out.

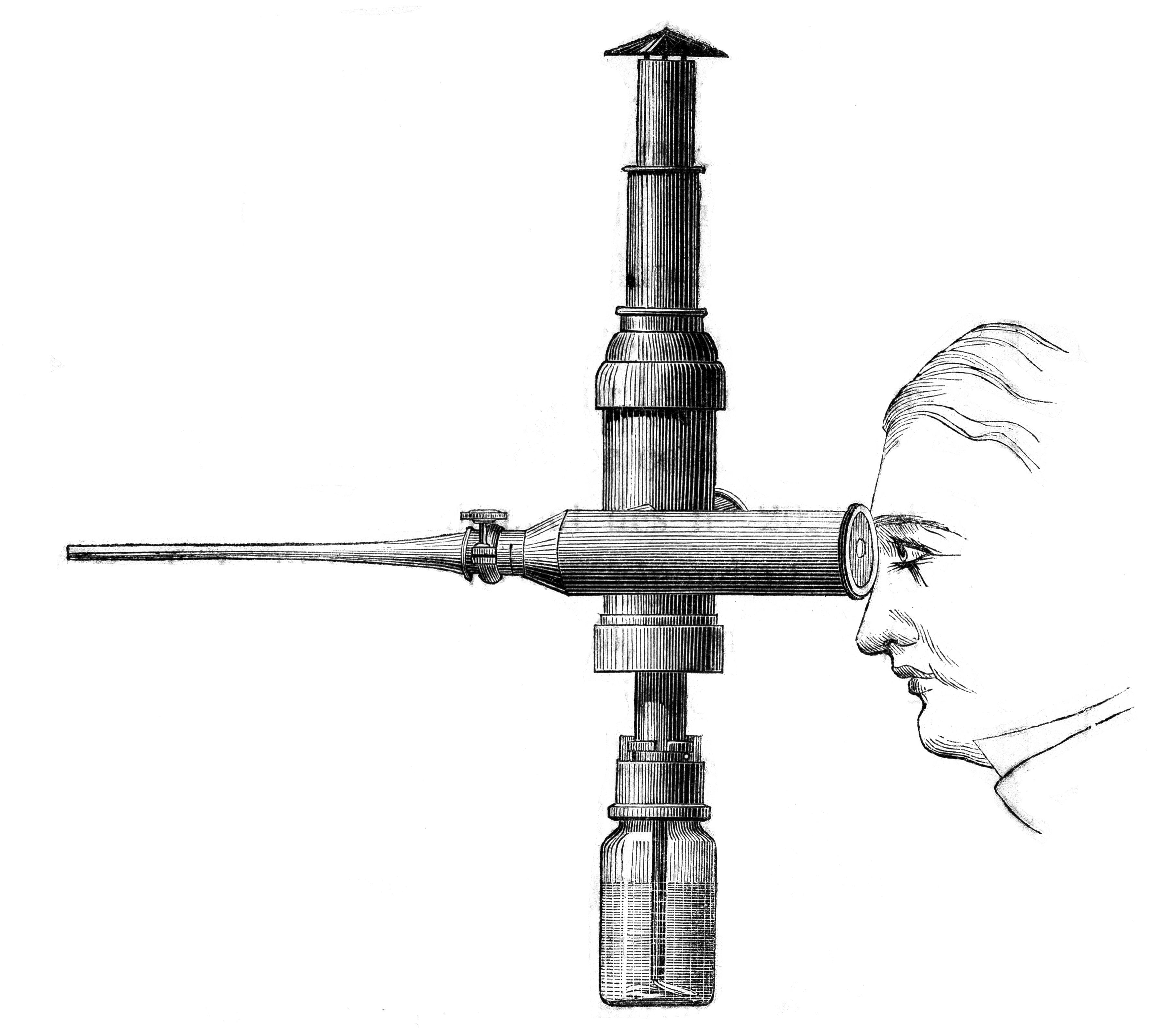

This desire expressed via the baroque folds penetrating the flesh, further reverberates as a scientific curiosity to peek inside the body via the 19th century invention – the first primitive endoscope by Philipp Bozzini called the “Light Conductor”, which after half a century was advanced by Antonin Jean Desormeaux. The use of endoscopes in medicine to look inside the body has preceded the discovery of X-ray, which later has promised the ultimate vision rendering the invisible thus the unknown side of the body as transparent. According to Lisa Carthwright, ‘at the turn of the century, lights were inserted in interior spaces like the bladder, the gastrointestinal tract, and the vagina to illuminate the tissue of organ walls from within much as a light bulb illuminates a lampshade. […] the use of light transillumination for imaging and diagnosis prefigures and parallels similar uses of the X ray, with an industry forming by midcentury around the production of various types of endoscopic devices and procedures based on this early technique.’99 Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body (University of Minnesota Press, 1995), p.113. It is important to acknowledge that the X-ray development took place at the same time as an invention of cinema, as Carthwright observed, scientific X-ray motion studies reveal the importance of the scientific and medical gaze in the development of the cinematic apparatus. It exposes a long-standing physical relation between the body, the image, and the screen, which ‘is grounded in a Western scientific tradition of surveillance, measurement, and physical transformation through observation and analysis.’1010 Cartwright, Screening the Body, p. 4. This desire is also visible in the early cinema of attractions itself, which embodies an analytic gaze to look inside the body. It can be illustrated with Menotti Cattaneo’s “anatomy lesson” – it is a performative spectacle followed by the film screening in which Cattaneo performs as a surgeon who is dissecting the human body anatomically reconstructed in wax. Giuliana Bruno noted that this spectacle taking place in Naples was ‘the predecessor of cinema’, which already exhibited ‘an analytic drive, an obsession with the body, upon which acts of dismemberment are performed. […] This corporeal desire [cutting, dissecting, reassembling] is strongly instantiated in early cinematic forms, which were obsessed with investigating and performing acts upon the body.’1111 Giuliana Bruno, Streetwalking on a Ruined Map: Cultural Theory and the City Films of Elvira Notari (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993), pp. 59-61. Desire to penetrate through the body as a living garment, illuminate it as a darkroom, or turn it inside out to unveil the ‘hidden’ secret of the living system, can be further explored in relation to the cinematic screen.

/Inside Out

[…] the film turns inside and outside itself and back again, swallows itself up and spits itself back out […].1212 Jennifer M. Barker, The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 158.

For Nancy, the skin is the truth, which allows to approach a body outside the terms of totality, delineating boundaries and terms of inside and outside. It is an assemblage of surfaces: ‘A body is an image offered to other bodies, a whole corpus of images stretched from body to body, […].’1313 Nancy, Corpus, pp. 119-121. According to this logic, fragmentation of bodies, which the cinema has actively contributed to by framing and cutting them, allows to glimpse at the body not as interiority or substance to be penetrated in search for essence, but its exteriority as its truth: ‘if we open them up, dissect, X-ray, scan, or hugely magnify them we are simply creating another exterior surface or relation of contact-separation of sense’.1414 James, The Fragmentary Demand, p. 143.

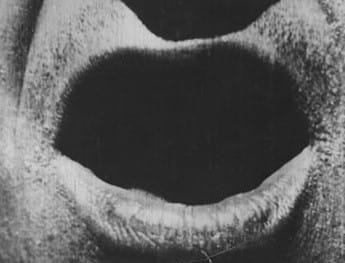

At the turn of the century, the film itself acquired a body by merging the screen, the human body and the apparatus into a surface which turns itself inside out and back again. While Georges Méliès in The Man with the Rubber Head, also known as A Swelled Head (L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc, 1901) experimented with his living head, swelling its duplicate to a gigantic size by a pair of bellows, The Big Swallow (1901) by James Williamson acts as a metaphor for the duality of inside and outside to consider the body in terms of exteriority. In The Big Swallow – a striking example of an early use of a cinematic close-up – an irritated man approaches the cameraman to devour him and the apparatus in resistance to the ‘swallowing’ nature of the camera-eye. This act leads to a complete absorption of a cinemagoer who is also swallowed by the screen-orifice. For Jennifer Barker, The Big Swallow illustrates an intimate and reversible relation between the object and the subject: it ‘is a comic visualization of Merleau-Ponty’s notion of the chiasmatic “intertwining,” in which “there is not identity, nor non-identity, or non-coincidence, there is inside and outside turning about one another.”’1515 Barker, The Tactile Eye, p. 158. Constant oscillation between ‘here’ and ‘there’, the inside and the outside, which opens up the body for tactile structures while balancing on the threshold, for Barker is an exposure of ‘the fabric of the film experience’.1616 Barker, The Tactile Eye, p. 161. Barker’s interpretation of The Big Swallow is illuminating in her attempt to communicate the corporeal and reversible nature of the cinematic perception through an ‘anatomical journey’ under her own skin described as a tactile contact, which ‘moves all the way through the skin, musculature, and viscera, so that we are inside the film and outside it at the same time’.1717 Barker, The Tactile Eye, p. 160. She also terms it as co-insiding with the film, which literally takes us in and we take it inside, exposing mutual incorporation of the outside through the act of swallowing which generates a sense of tactility through continuity.1818 Barker, The Tactile Eye, p. 160. Tactility here acquires an interpenetrative quality, evoking fusion, immediacy and presence, which in Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s ontology of flesh is denoted as a sense deeply penetrating the matter through which the world is disclosed as a connective tissue. Although the concept of flesh attempts to overcome mind and body, spirit and matter dualisms, it does so through an interior perspective of the seer projecting toward the world.

Tom Gunning turns to The Big Swallow to expand on Barker’s account of a self-ingesting film, suggesting that the figure of swallowing ‘may serve as a particularly powerful image for our relation to the cinema as viewers (and the cinema’s relation to us)’ because of its technological dimension.1919 Tom Gunning, ‘The Impossible Body of Early Cinema’, in Corporeality in Early Cinema: Viscera, Skin, and Physical Form, edited by Marina Dahlquist and others (Bloomington: Indiana University Press (ProQuest Ebook Central), 2018), pp. 21-31 (p. 25).

20 Gunning, Corporeality in Early Cinema, p. 30.

21 Gunning, Corporeality in Early Cinema, p. 29.

22 Gunning, Corporeality in Early Cinema, p. 24. The impossible body emerges through a process of continuous exchange ‘between the inside and the outside, between what can be swallowed and what can be projected outward’20, which ‘extends and transforms the affordances of our natural body.’21 The devouring screen becomes ‘the space of metamorphosis’22 exposing a viewer to a mode of plasticity and the protagonist’s polymorphism. Gunning takes into consideration a complex human-technology relation alongside the filmic experience discussed by Barker, but still follows a similar idea of projection of the being outside itself which evokes such relation as prosthetic. This complex relationship between the cinema’s technological body and a viewer is further elaborated in Pasi Väliaho’s analysis of The Big Swallow, which he approaches through Ernst Kapp’s concept of '“organ projection” (Projection del Organe / Organprojection) that signals the way in which our corporeal apparatus, the inside, becomes exteriorised in technical objects.’2323 Pasi Väliaho, Mapping the Moving Image: Gesture, Thought and Cinema Circa 1900 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), p. 80.

24 Väliaho, Mapping the Moving Image, p. 81. The organ projection refers to the blurring of distinctions between inside and outside, and ‘postulates a veritable feedback system between the living and the technological, similar to that of the one that exists between living organisms and their surroundings.’24 It is also noticed that with regards to biopolitical modernity the idea of ‘organ projection reflects technology’s emergence as a kind of quasi-natural environment’ with no hierarchical distinction between the technological and the living beings.2525 Väliaho, Mapping the Moving Image, p. 81. Having in mind Kapp’s concept of projection, for Väliaho The Big Swallow performs an inverted organ projection: ‘the outside environment (the screen) becomes the inside of the body and consciousness, while the latter lose their coordinates and turn into any-point-whatever’s in the cinematic space’.2626 Pasi Väliaho, ‘Bodies Outside In: On Cinematic Organ Projection’, Parallax, 14:2 (2008), 7-19, (p. 12).

27 Väliaho, Mapping the Moving Image, p. 89. According to Väliaho, ‘the result is a technologically generated “ahuman” perception that is multiple, constantly changing and becoming other.’27 It could be said, The Big Swallow exposes alterity at the centre of the self which challenges the logic of interiority.

The in-between space opened during a one-minute-long sequence has revealed to the audience in 1901 a sense of an open-ended relation between material bodies and technical apparatuses that allowed to experience the event of being as a spatial-temporal event, a contortion of established boundaries between there and here, inside and outside. In The Big Swallow, the act of swallowing exposes us to an ‘“originary technicity” – ‘the sharing of embodied sense which gives us a world […] as a technical-mechanical relation (of sense) between material bodies, or partes extra partes, and as a means of disclosing material bodies in the contact-separation of sense and matter.’2828 James, The Fragmentary Demand, p. 144.